The Mutus Liber, which translates to “Silent Book” in Latin, is a famous alchemical book that was first published in France in the late 17th century. It is a collection of 15 engravings or plates that depict the process of creating the Philosopher’s Stone, a legendary substance said to have the power to transmute base metals into gold, as well as to grant eternal life and other supernatural abilities.

Unlike most other alchemical works, the Mutus Liber contains no text or explanation to accompany its images, hence its name. The author intended for the images to speak for themselves and to be interpreted by the reader according to their own understanding of alchemy – instantly, bypassing verbal thinking.

The same aim was later held by many artists who created abstract, visionary, surreal works. A lack of subjects and objects which could produce a convenient textual narrative for the viewer was supposed to generate an impulse for the creation of the viewer’s own emotional response.

Quite often we think about visual imagination as something which complements verbality, but frequently it helps us to bypass and replace verbal utterance to appeal to our sensory experience, and emotional intelligence, stimulating imaginative thinking.

Non-verbal visual imagery helps us to communicate and understand information beyond words. A picture can convey complex emotions, thoughts, and ideas in ways that words alone cannot.

A picture can be a helpful and sometimes indispensable way to convey something which exists beyond our conscious mind and helps to give form to the subconscious, or – to our dreams.

I am convinced that everyone who tried to describe their dreams in words encountered some sort of difficulty as dreams exist in different realms and follow different logic. It feels that describing a dream is like catching a fish which moves on the very bottom of the ocean with a shallow net.

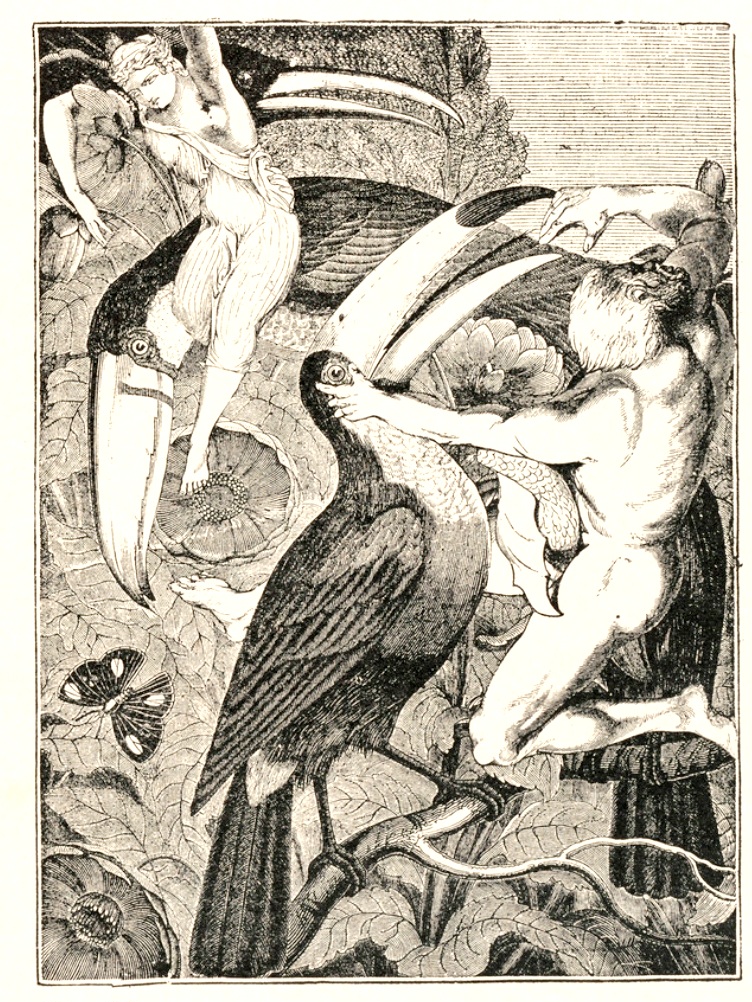

To depicture dreams Max Ernst created his surreal collage novels which can be one of the first examples of a narrative told through collages. Ernst combined various visual elements, including illustrations, photographs, and found images, to construct a fragmented narrative which follows a logic of a dream. For example “La Femme 100 Têtes” (“The Hundred Headless Woman”) published in 1929 tells a story of a man who discovers a woman with multiple heads and proceeds to decapitate her 100 times.

Another Max Ernst collage novel – Une semaine de bonté (“A Week of Kindness”) comprises 182 images created by cutting up and re-organizing illustrations from Victorian encyclopaedias and romantic books.

Those collage stories followed exactly that – a dream logic – they brought us familiar images in strange, unpredictable sequences or circumstances blurring the boundaries between reality and the subconscious.

As usual, dreams manifest our fears and desires, and Max Ernst’s collage works do the same.

He taps into the absurd, erotic, and the uncanny. Can it be described in a logical way in which we usually communicate verbally? I don’t think so.

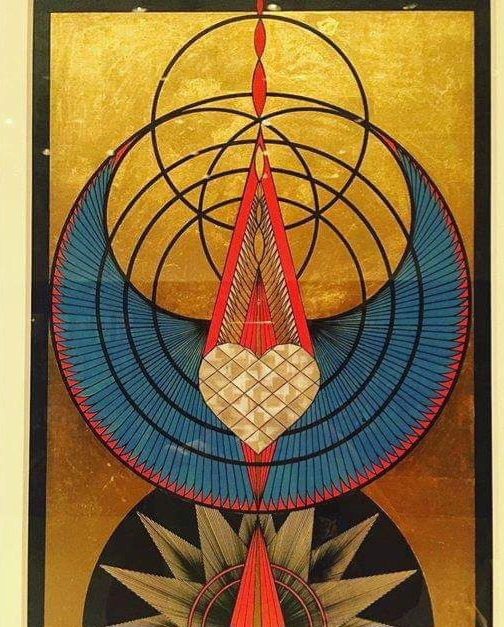

Another, perhaps more obvious example of extreme non-literal non-verbal and non-objective is abstract art as such. It does not attempt to represent the physical world in a literal way but uses colour, line, shape, rhythm, and form to create compositions that are open to interpretation without the literary “meaning” – i.e. descriptive narrative.

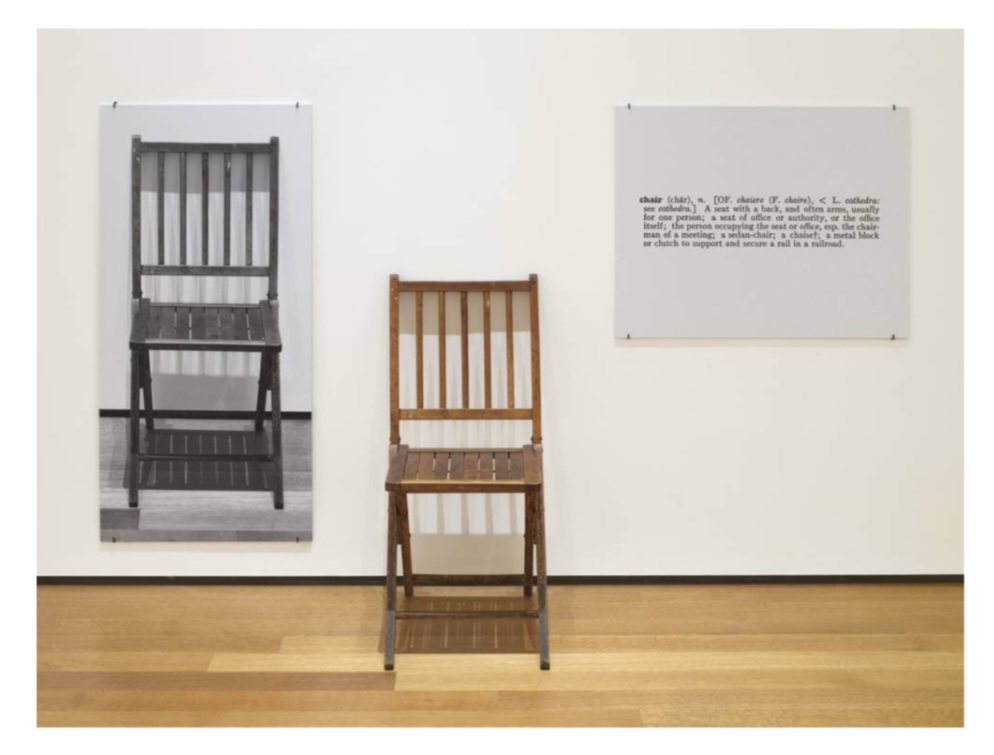

Interesting, that in conceptual art things might work in quite an opposite way – these textual narratives can be more important than the art object itself. It became a common practice for artists to include descriptions of the concepts behind their artworks. Some people like it, because it’s kind of gives more substance to the concept and makes art more accessible to the public (i.e. explaining in words what the artist wanted to say), while some people – don’t like it as they think that visual art should speak for itself without a textual crutch.

When art moved away from the representational traditions it became “meaningless” for some people. I think it happened because they were not willing or able to pin a descriptive story near visual images or sculptural forms. Just a colour, just a form, just a shape, just a texture, just a composition without the possibility to tell a verbal story felt lost, however not always and not for everyone. Sometimes not despite the lack of such a textual part, but thanks to the lack of it – a work of art can convey an emotion in an especially strong direct way – bypassing the viewer’s inner critic. It’s like an artist sends a viewer an emotion or a feeling and it goes straight to the viewer’s soul – without the textual door guard security.

I know there might be a million examples, but I’ll bring just one – Mark Rothko, an abstract expressionist. Not because he’s my favourite artist ever, but because I was born in the same town as he – Daugavpils, Latvia – and in this town now there is a huge Rothko Art Centre.

So, naturally, I developed an interest in his art but wasn’t a huge fan until… until I sat for about 40 minutes in Rothko Room staring at the huge maroon canvass (or was it a panel?). It was in London, but I was somehow gradually transported to Daugavpils, and not just a town, but to my own personal Daugavpils where I was totally depressed and where there was a constant November, wet snow and sleet and where one long poignant note sounded in the chilly air – produced by an old tram painted in maroon which was moving through the town as a ghost.

Rothko was very depressed. I was very depressed at some point in my life. Somehow sharing space with the huge maroon thing brought me to this time and place. (By the way, I am sure that Rothko’s depression was connected to Daugavpils too, but it’s another story for another time). It was intense, it really was.

Was there a tram in his painting? A town? Any object? No, there was just a colour, well, more precisely – a combination of red-maroon-dark red. But my soul made the journey where Rothko intended to. At the time of this experience, I didn’t know that Rothko believed

that art has the power to transcend the material world therefore a painting can be a portal into a transcendent reality, and a colour – a vehicle able to transport the viewer beyond the physical world.

I tried this journey, and it works.